A Gift to Birobidzhan, 2009

Visit the official project website here.

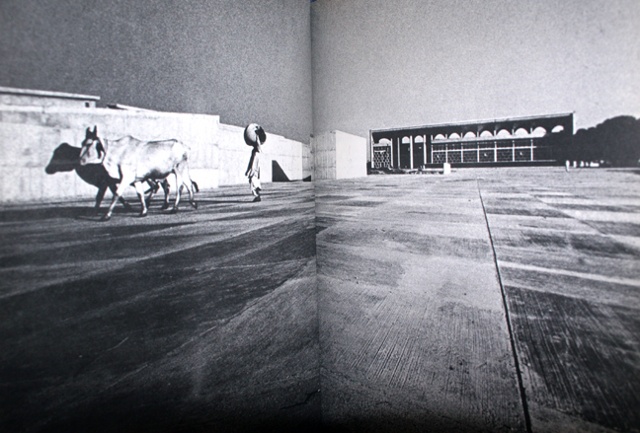

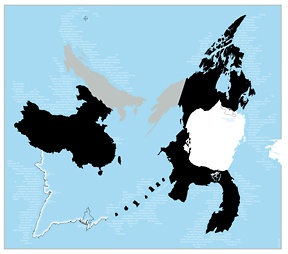

Birobizhan is a city and the administrative center of the Jewish Autonomous Region within Russian Federation, located on the Trans-Siberian railway in the Far East, close to the border with the People's Republic of China. Following Lenin’s nationalities policy, which encouraged each ethnic group to settle in its own territory and develop language and culture “national in form and Socialist in content,” the Jewish Autonomous Region was established in 1934 with Yiddish as its official language and was supposed to become a home for the majority of Soviet Jews, solving the “Jewish question” in the Soviet Union.

At the beginning, the Birobidzhan project attracted a number of Soviet Jews as well as many from abroad—including from such countries as Argentina, the United States, and Palestine—who came to Jewish Autonomous Region to help build a secular Socialist Jewish homeland. In the long run. the Birobidzhan experiment was unsuccessful in attracting the majority of Soviet Jews. Many newcomers left Birobidzhan demoralized by Stalin’s purge of the region’s leadership in 1937 and by the inhospitable Taiga climate. The Jewish Autonomous Region and the city of Birobidzhan still exist today, with only five percent of its inhabitants (about 4,000 people) being Jews as of 2007.

In 1936, at the height of international enthusiasm for Birobidzhan, two hundred works of art were collected by activists in the United States to serve as foundation for the Birobidzhan Art Museum. The collection included works by Ben Benn, Stuart Davis, Adolf Dehn, Hugo Gellert, Harry Gottlieb, William Gropper, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Raphael Soyer among others. The collection was first exhibited in New York and Boston. In late 1936, it was shipped to the Soviet Union, but never reached its final destination.

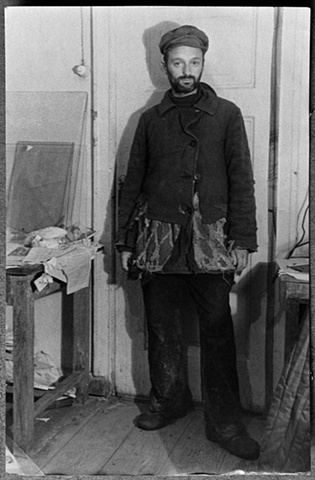

In 1937, a group of Chicago-area artists created a portfolio of woodcuts entitled, “A Gift to Birobidzhan,” as a fund-raising project for Birobidzhan. The participating artists were active in the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression and their works in the portfolio displayed images of oppression and despair as well as of hope for “new life.” Among these artists included Mitchell Sirotin, Alex Topchevsky, Todros Geller and others. In the introduction to the portfolio, written in English and Yiddish, the artists stated:

“We, a group of Chicago Jewish artists, in presenting our works to the builders of Birobidzhan, are symbolizing with this action the flowering of a new social concept wherein the artist becomes molded into the clay of the whole people and becomes the clarion of their hopes and desires.

We feel, welling up in our hearts that need for our coming forth and mingling with our brothers in order better to understand what dreams are stirring in their breasts.

Thus we will better translate, in our media, these aspirations for a new and better life and pour forth, to a more understanding world, from our fountain of creation the first sparkling glimpses that are the new Jew in the making.“

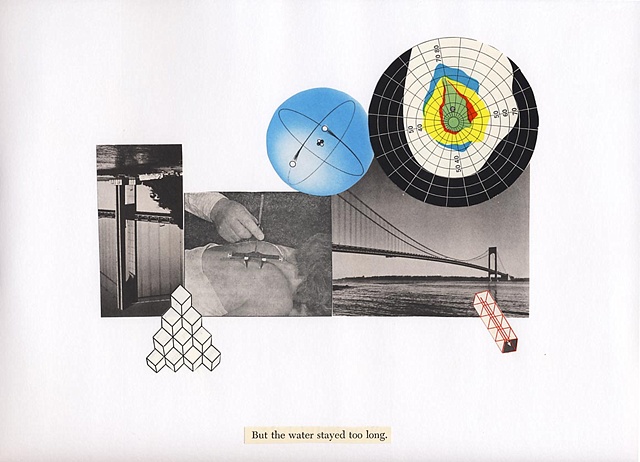

My project, “A Gift to Birobidzhan” is informed by the two historical gestures of giving to Birobidzhan – the art collection for foundation of Birobidzhan Art Museum (1936) and the “A Gift to Birobidzhan” woodcut portfolio (1937). My project is an attempt to responsibly and meaningfully repeat seventy years later the gesture of “a gift to Birobidzhan.” I’m asking a number of international artists to donate a piece (of art or otherwise) of their choice for inclusion into the collection “A Gift to Birobidzhan” of 2009.

With this project, I aim to continue a dialog on the legacy of the Russian Revolution and Soviet experience in relation to Lenin’s nationalities policy and the issue of national self-determination and autonomy within leftist political discourse in general. This project revokes the utopian promise of Birobidzhan, a Socialist alternative to Israel, as a point of departure for discussions on 20th century’s impossible histories of territorial politics, identity, Communism, national self-determination, and a common “seeking of happiness.” Dreams for better days, collective identities, and universal motifs of social justice in “A Gift to Birobidzhan” are to be informed by the experiences and histories (in different parts of the world) of the seventy years that passed since the first gestures of giving to Birobidzhan took place.

Selected Bibliography

Louis Proyect, A Gift to Birobidzhan, The Unrepentant Marxist, September 2014